I turned from the entrance at The Café in Naples, and almost knocked her over, plates and all. I grabbed the tray and held it with one hand, and her arm with the other, and lost not a glass. She was on my weak side, a few inches under 5 feet tall. I could tell she was embarrassed, so I apologized for my clumsiness. I thought of a tray I dropped onto a table at Jack Hackett’s on Hoods Pond in Ipswich, Massachusetts while a bus boy, 15 or so years old. The man at the table, whose dinner I destroyed was a gentleman to me. I remembered his lesson.

When I got to my table on the sidewalk just off 5th Avenue, she came with water.

“Where are you from?”

“I am from Guatemala and this is my second day,” she said proudly, not here long enough to balk when a Gringo asks such a question. She was likely in her early 30’s. Her English was just good enough to be called broken. She looked more indigenous than Spanish, her face round and dark.

“I am pleased to meet you. I come here often. My name is John.”

“My name is Maria,” she said with a bright smile.

“I am glad you are here, Maria. America needs people like you.”

“I am a hard worker, Mr. John.”

Interesting that she felt it necessary to say so.

“I can tell that you are.”

I couldn’t tell her how lazy I think a lot of American’s are, and how I fear that the culture of laziness, combined with government support, may well destroy us.

I suspect Maria knows fear. Why else would she be here? She knows she has to work to survive, and is grateful for the chance. I know fear, but for the most part, a different kind. Much of my fear was self-imposed, and thrilling. Whenever it was about survival, it was never fear of starvation. Fear, for me, has kept me vital and reaching for life. Life without fear would seem…not enough. Maria does not know or understand the kind of fear I thrive on. My ancestors in the 17th and 18th centuries knew the fear that brought Maria to America.

I did not tell her that without people like her, Florida would collapse. Many of my Latin friends know that young Gringos won’t do the work they do willingly. They don’t have to. Maybe they should.

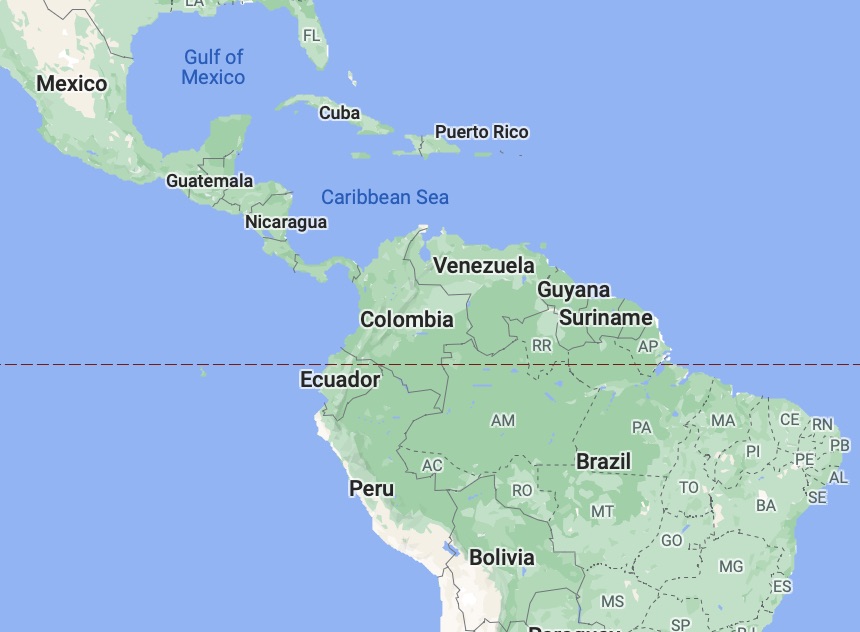

Years ago, I sailed my boat into Marina Hemingway in Havana, Cuba (against U.S. law) on my way to Panama, paying off Cuban officials for inspections and stamps upon entry. I took baseballs, fishing hooks and line to give away and make friends. I heard jokes about Fidel, just as we might hear of our elected leaders. The marina still had pictures of Hemingway fishing big game with Fidel. His essence was still there, but the marina was run down, several boats having been lifted onto the hard decades ago, left to rot in a field of weeds. What was and could once again be a beautiful marina is only a two hours from Miami in a powerboat and a twelve hour beam reach, an easy sail to a magnificent country, culture and music, ruined by gangsters who fail to recognize the power and creativity of people living and working with a Republic constrained by a constitution.

There was a guy I paid to help clean my boat. He was an engineer who never had the chance to work as one. He told me about the pitiful government check he gets each month that must be supplemented in the black market and doing jobs such as cleaning my boat. He had two children, also educated as engineers, he knew had little opportunity in Cuba. I could see in this man that the dignity of work was still alive, in spite of a corrupt government.

Cuba is an easy place to love, and Cubans are easy to like. How is it that such good people can be so constrained only 90 miles from Miami?

I am friends with a guy who lives in Oklahoma. His father came to New York from Cuba with little education in the 1950’s. As a Cuban, he made a meager living rolling cigars. As an American, he owned three dry cleaning stores in The Bronx and became a Yankee’s fan with his son, now the director of quality for a company in the energy business.

We don’t know enough about these stories. We are too far removed from the stories of the good people who come here for freedom we take for granted.

A couple of weeks ago, I had breakfast at one of my new favorite places in Naples, a French bakery owned by a woman from Dominican Republic and a man from France.

Two of the waitresses are twins. Of course, I have managed to learn a bit of their story. They are 26, from Argentina, pretty, smile all the time and have two jobs each. They are not permitted to go to school yet. The government is standing in the way. In February when and if they get the proper papers, they plan to get degrees in finance. I will give good odds that they will find a way and do well. As I well know, starting college in one’s mid 20’s can be an advantage, starting from a point of maturity developed through years of work.

I suggested that they think about what they want to do, then get the education they need to do it. It is a subtle difference, but important. There are a lot of Latin people here who work hard and might need help learning to manage money and send it home without being ripped off with usury fees. And it might be more lucrative and rewarding than getting a few old rich white clients.

I hope I get to know more of the story of the twins. As I have written before, I love to spend time with people who are not like me. I have come to love people from around the world who have little, but always have a smile and a bit of hope for tomorrow. They teach me, and influence my life, bringing out my gratitude and hope, and remind me how lucky I am just to be alive. They tell me how easy it is to live in the United States and how lucky I am to have been born an American. I know that; I am afraid many don’t, mostly those who have seen little or nothing of this wonderful world. I am lucky to have traveled and seen so much and met so many people who are not like me.

My dance teacher is from Colombia, has three jobs, loves it here and thinks Americans have no idea how easy their lives are. One of her jobs is a waitress. She gets nice tips because her brilliant smile, kindness and zest for life is rewarded by her customers. She is patient as a teacher; I know, as I am a slow learner. She has a master’s degree in business from a university in Colombia, an undergraduate degree in physical education and dance. She is an athlete and did extreme sports in Colombia and sold her studio to come to Florida. She belongs to a group of dancers, all Latin, preserving her art and culture with native costumes, performing in much of Florida with her gang of dancers and friends. She knows hard work. I had a late lunch on Christmas Eve with a friend and dance partner where she works. After working all day, she left at 4PM to drive six hours to be with her family in Jacksonville. Her pictures on Facebook are always full of life, smiles, family and friends.

I love her stories, and love to see the small things that please her. A neighbor gave her a ten inch Christmas tree with only a ribbon as decoration. She loved it! When she showed it to me, it reminded me that simple things matter the most, if they come with a smile and maybe a surprise.

I know another woman from Colombia who owns a high-end hair salon with several employees. She has a black belt in karate, takes boxing lessons, lots of dancing lessons, is single and has two kids. On Friday she often shows up at a dance club at 10PM when it opens (I am just about done for the day by then) dances with all the good dancers, wears them out, and leaves before midnight. She has to get up early for work on Saturday. She is kind to everyone and always has a smile even though she only has a few hours a night for sleep. She even dances with me once in a while.

There is a Cuban guy I know who teaches dance lessons. He taught in Europe, then for some reason, taught in Maine. His lessons are supposed to last for an hour. He never stops on time, and his lessons always seem like a party. I would like to get to know his story.

Who are these people I get to meet? I never hear about them on the news.

I talked to a young man in Canada last night who I met in Panama several years ago. He loved hanging out on my sailboat, having a chance to talk to an American. I remember when he was about 15, his aunt told him he had to work the cash register in her store for the day because one of her employees didn’t show up. He complained that she was mean and was torturing him. He wanted to go to the beach and hang with his friends. I pulled him aside and we had a chat, the first of many. I bought him a few beautiful notebooks in England, not the cheap spiral-wound kind with advertising. If your thoughts and notes have value, collect them in a book you want to take care of. He had not seen much of the world. He is in Canada for school, but cannot get a visa to travel to the USA. I want to invite him to my house in Florida once it is finished. I hope he can visit. I like to think my stories of work, travel, sailing and science and engineering influenced him a bit. He is in Alberta, Canada this December, experiencing real cold weather for the first time, while earning a master’s degree in environmental science in English, his second language. He told me about the long list of equations he has to memorize, and we laughed because only two or three matter. He grew up near the ocean and hopes to save the planet, a noble goal for a young man. Like many Latin people, he has a close family, which I envy. I have been to gatherings with his family, large gatherings with lots of food and closeness.

This young man from Panama did ask me how I was enjoying retirement. I said I will never retire. I was asked by a client a couple of weeks ago how much longer I will work and I said until a week or so before I die. Work gives me worth, because my work gives me the opportunity to teach engineering while telling stories about the history, and value of work.

I rented a condo several months ago through December because my house was supposed to be finished by then. Now it looks like it will be the end of June, six months late, so I had to find another place to live. I got a message on Facebook messenger, called at 8AM and paid the rent for January by noon. Rental property here in Naples is outrageous, and will only be on the market for a few hours. The landlord is a Russian woman, a urologist, who gave up medicine to have a better life here for herself and her son. She owns and rents a couple of condo’s. When I asked for the WIFI password, she texted a stock symbol. I asked about it, learning she had paid cash for the condo from the appreciation of the stock. I told her she is a good capitalist and not much of a communist. She didn’t quite smile. It wouldn’t be very Russian. Russians are not as friendly as Latin people but I did manage to get her to talk a bit with a few of my own stories. She finally did smile. Perhaps if she took dancing lessons from the Latin folks?

The unbuilt house I bought eight months ago just had four red stakes with flags driven into the ground a few days ago! Progress! The builder cannot get timely labor, windows, cabinets, wood or cement. My house is seventeenth of twenty to be built. They are all behind by half a year or more.

I took a ride to the site to take a look a couple of months ago. The blocks for most of the houses through number 14 were finished. I stopped to have chat with the workers who were on break. It is amazing to watch these guys. The blocks are dead straight and aligned. They can place 1000 blocks for a house in under a week. Only one spoke much English, likely the sub-contractor. I made a comment as to how the work would take twice as long if he had Gringos on his crew. He translated and the crew laughed. I asked about the women on the crew. A few of the workers bring their wives to carry blocks, 35 pounds each, one in each hand.

The framing crews are always a couple days behind the blocks, if they can get the wood. Few of them speak English, and the work is done in short order. I have not seen one person laying blocks or on a framing crew who were Americans. I did see a plumber pulling water lines, standing on a ladder with sneakers on. Who does that? He has since quit and the builder hired another plumber from Miami. I wonder if he is a Gringo?

The Latin guys bring their wives to work for more than just carrying blocks. One woman learned how to run a crane to lift the roof joists so the framing crew could go faster. Other women paint and plaster, and lay the floors.

The guy who does the pools is Latin, and hires only Latin crews. He knows they will show up and get the work done. He told me that he offered some homeless guy $100 cash to pick up trash for a day. He refused.

Not long ago I went to the dealer where I bought my car a couple of years ago and got the service woman engaged in a chat. Cars have been waiting for sheet metal parts from the UK since April. It seems the factories have been opened and closed so many times, with staffing and layoffs so frequent, that the employees don’t think it’s worth it to show up. Why bother? As soon as someone gets sick they close down. And the government pays them to sit around.

We will be dealing with the damage to our culture for years, but we won’t fix it unless we admit that it is.

Even with parts, the dealer claims it is still hard to get the work done. Though short of workers, they still had to let one-armed Jimmy go. Oh, this had nothing to do with Jimmy being disabled. He had two arms but one was dedicated to his phone.

My father once told me that a man is placed on this earth for one reason and one reason only; to work. I think I was about 15. We were finishing the basement, putting up walls, pulling wire, hanging sheet rock, and painting. It was so long ago we had to drive nails with a hammer and cut wood with a handsaw. You drove nails, as there were no guns, and the saw was the kind you had to push back and forth. It was good for me. We never hired anyone for the jobs that any and every man should know how to do. I don’t even know if you could hire someone in those days. Got work to do? Get to it!

Maybe what my father said about men and work tells more about him growing up poor on a farm, and my grandfather who worked hard and died with his dignity intact, than what it means to be a man. Maybe a man is here for more than work, but if a man does not know work, work is not ingrained in who he is, then he is no man. If his culture does not value work, then his culture is broken.

A man should know certain things. A man builds things, fixes and takes care of things. Work gives a man a sense of, well, being a man. He can cut down a tree, plant a garden. He knows the pride of harvesting and eating what he has grown, even if only a garden, and putting it on the table. I had my first car at 16. It never entered my mind to take it to a shop. I learned more than one hard lesson while figuring things out by myself, making mistakes and slow progress, but I remember the pride and dignity of driving a car that I fixed. I did it!

I was working with a friend changing the engine out of a car at 16 or so. We almost pulled ceiling down, using a couple of rafters to attach a hoist. The first time I almost killed myself was changing the leaf springs. I nearly dropped the axel onto my head, only suffering a scratch to my scalp.

If a man does not know work, he is useless to a woman, and should not have children.

I was at the eye doctor a couple of weeks ago. He is from Yugoslavia. His wife, who is from his home town, is his assistant. He always seems to be in a hurry with the other patients, but when I go to his office we end up talking more than checking my eyes. This time, he started with a question about the politics of Covid. I gave an answer much like a politician, revealing little, deferring to him. He knows I like to tell stories about things I have done and seen around the world, and how I choose to live with my new heart. He told me about the kids he sees with myopia because they spend too much time staring at a screen, and how much worse it is since Covid lockdowns. I could tell he was frustrated. Too many kids, he says, have diabetic retinopathy (I had to look it up.) His daughter is a surgeon in Jacksonville. He complained about the long drive to visit her. They must love the visits; they go a couple of times a month. Kids, she says, have the vascular systems of people in their 50’s from being locked up while staring at screens and eating poison food while in Covid prison.

I told him that I know of more than one company that suspended drug testing since factories have reopened. Americans are so drug addicted that testing would cause an economic burden, making the supply chain problems even worse.

I worked in a factory in Kansas this year. One guy was born this century, making me feel quite old. He, like many of the others, wore steel-toed cowboy boots and a huge belt buckle. The guy who was born this century raises and trains horse with his dad. It might be years before he knows the gift he received, working with his father. These farm kids know the dignity of work. I have worked with a lot of people, men and women, first generation off the farm, for the past 50 years. They know work. It is in their blood.

On a day off, I found my way wandering down a dirt road in South East Kansas, not far from the Missouri line to a pig farm. I met a 14 year old boy who was digging a ditch to run wire to a birthing shed for pigs. He lived in a mobile home with his father and younger brother fifty yards or so from the pigs. They had a tough year. One field was planted in pumpkins which they could not harvest because they lost a couple of weeks to Covid. They put up a sign and let people take the pumpkins. I guess the pigs got the rest.

The boy stuck the shovel in the wet muck, walked toward me like the man he would become, stuck out his hand to firmly shake mine, looked me in the eyes and introduced himself. He showed me the pigs, announced how proud he was of the prizes they won at the state fair. He was a big kid for 15, so I asked if he played football. No, he did not, and had no time for such things. He was working with his congressman to stop tobacco companies from advertising to kids. His dad had mixed emotions about the boy leaving the farm, having spent part of the summer in Washington as an intern for his congressman. Such families have to sacrifice when one member has lofty goals beyond the farm. “I plan to go to law school, and run for governor. After a couple of terms, I hope to run for President,” he proudly announced to me.

I looked him in the eye, and saw something. “I suspect you will do just that, and the country will be better place with a man like you in charge. I wish I would be alive to see it.”

From October, 2016 until October, 2017 I was, for the most part, in the hospital in Orlando. I received the Gift of Life, a new heart, on September 25, 2017, and walked from the hospital twelve days later, just a year after I arrived. The people who took care of me were from the Middle East, India, the Caribbean, Puerto Rico, Haiti and Cuba. More than half of the many people who saved my life were either not born here, or their parents were not. Without them, as well as the hardworking people born here, I would not be alive.

Too many American’s no longer know much about work, and have no model, while the government supports it. The model of work is right in front of us, our neighbors from across the borders.

We have massive student debt for degrees that do not result in useful work. Graduates are ripped off, idealistic until time to buy food and pay the rent. Why? They do not know the essence of work; they were not shown. No one said, “You are here to work, and work is life.” Many think they are entitled, refusing to admit that what they learned has no economic value and comes from a cultural void. They refuse to be responsible for their own bad choices.

Education can never be free or easy. If it is, you will get your money’s worth and value it appropriately. There must be a price to pay, one way or another. With no price to pay, you may well end up a slave to a government check, living a broken life.

The foundation of any modern first-world society is based on a large middle class doing useful and valuable work. No free nation has ever existed without a middle class that is educated, and based on families with a father who is a good man and a role model.

Our middle class is being destroyed. We have an education system that has failed, and a family structure that was doomed by Johnson’s Great Society in the early 1970s which started the rapid decline of two parent families.

Our culture is broken. The American system of education does not prepare 18 year old graduates to do much, if anything, of value. Those who can and do work, learned their skills from parents and grandparents, not from the broken education system.

Many of the immigrants coming to this country to work while Americans stay home, bring a model of family, a work ethic, fun and discipline. All? Of course not. Many shouldn’t be here, but the United States can’t even control who, or what, gets across a border.

There are a hell of a lot of people here without passports, and many are better Americans than we are.

Post Script: My good friend and former wife, Barbara Irwin-Allen was left a note by her mother on her death; “Work. Be Happy.”

Marvelous. Again. I am grateful that I still work at my crafts, playing guitar and writing. Work isn’t a hobby. Thanks for this, John. I had a 40-year career in the tech biz. I retired to spend more time at my real work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great story John, drew my attention from beginning to end.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great text, interesting observations and important conclusions. I always appreciate your comments, life insights and read all of them since we’ve met at Koblenz (TRW workshop )John.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your kind comments. I hope we get to work together again in Germany.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John,

Your writing and storytelling is now in stiff competition with your gift and talent for solving tough and complex technical problems.

I suspect hard work, drive and the early childhood lessons from your ancestors had something to do with it.

Please keep sharing these stories—they educate and inspire.

Regards,

Pedro

LikeLiked by 1 person

John,

Your writing and storytelling is entering into stiff competition with your gift and talent to solve tough and complex technical engineering problems.

I suspect those early childhood lessons from your father and grandfather about the importance of work and honing your craft had something to do with it :-).

Please continue sharing these stories—they educate and inspire.

Regards,

Pedro

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved the story!!! 😊… Thank you so much for what you say about the emigrants and about me. I really appreciate that you appreciate our hard work here as emigrants and you can see how value we are for this country and that you realize that Americans don’t have idea what lucky they are just with born is this beautiful country

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear John. As ever wonderful to read of your experiences and perspectives on life. I so agree with the importance of strong work ethics, and the importance of family influence. Peter and I continue living in Panama on our boat Cheetah. We enjoy the multi cultural nature of the place, and are pleased to call many of the local people our friends. Fond regards Jennifer and Peter

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was planning on visiting this month until the covid got out of hand. I will see you this spring. John

LikeLike

Beautifully depicted. Thank you for your dedication, love and time!

Heart of Gold 💛

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLiked by 1 person

what a great and interesting story just like this great interesting world God created

Where the same country can mean opportunity excitement and a better life to one human being. Yet someone born there can be critical wasteful and unappreciative. Same country same street maybe they even work at the same place. b

LikeLike